FREMONT THEATER, Feb. 7 — “They say that if you remember the 1980s, you weren’t doing it right,” – Dave Wakeling, frontman of The English Beat.

Upon immersing myself in the crowd, I wondered, was the smell of clove cigarettes, maybe an American pale ale and the feeble sting of someone’s “personal bouquet” better left in the past? The sins of “embroiled optimism” are something you’d leave behind, along with fleeting youth.

The two big B’s — beer and body odor — were undoubtedly present, filling the venue when The English Beat not only returned to San Luis Obispo but when many young hearts returned to The English Beat. These Rudys definitely didn’t remember the 1980s, but they would remember that night.

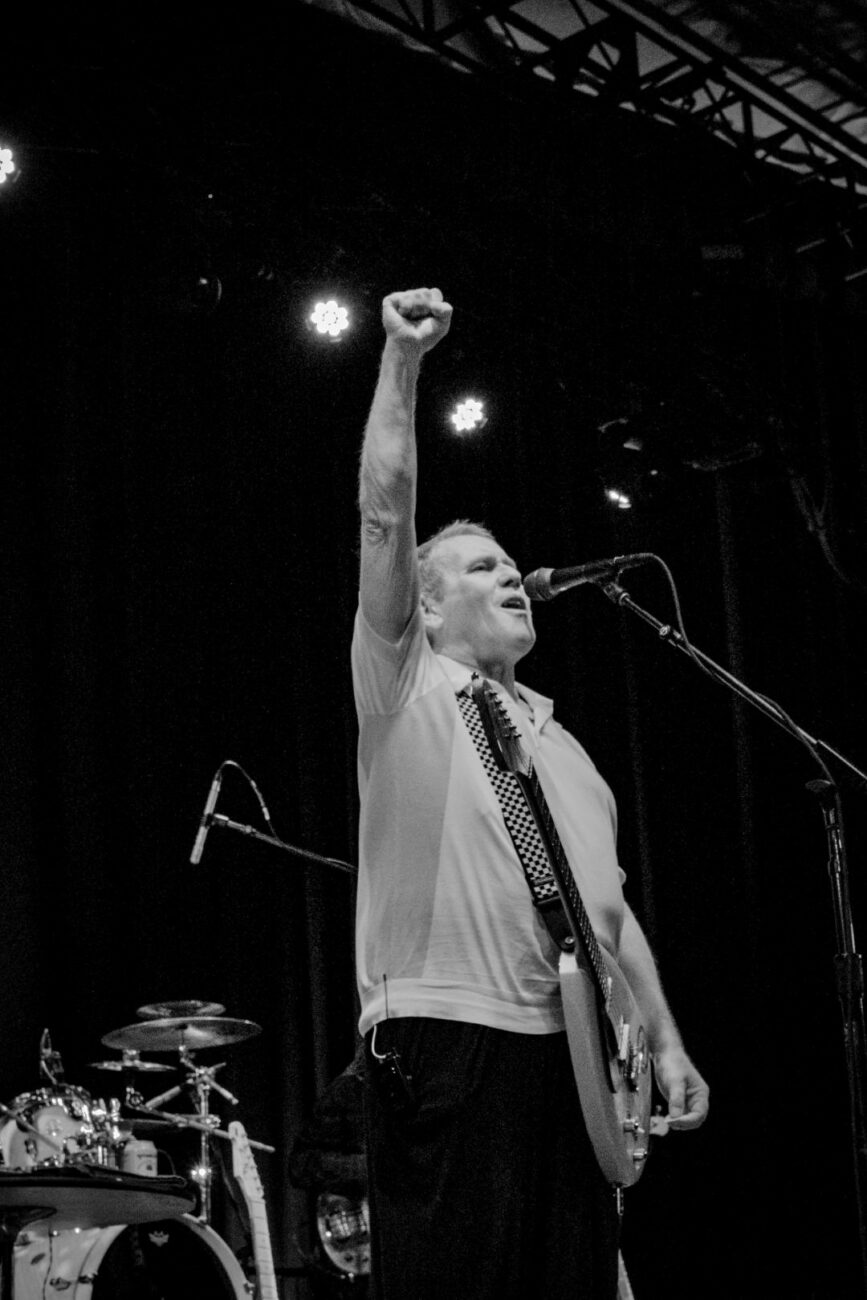

Wakeling, 68, is not your run-of-the-mill frontman. A lyrical genius and melody tycoon, wealthy not from years of touring but from creative novelty. That night, he performed a tribute to The English Beat, the band that later split into General Public. (An almost two-in-one deal for the attendees of the concert).

The older Two-Tone crowd was mostly made up of couples and siblings alike, aside from a small section of young people. My colleague and I, along with a few other faces I recognized, stood out. We were not the only adolescents in attendance… a tenderness filled the room — the kind only children pretending to be adults, or adults pretending to be children, could feel.

“I need a cue card,” Wakeling hymns, feeding applause before lamenting the loss of his bandmates with a series of matter-of-fact utterances, as if they had dropped like flies — swatted, then squashed. “First Saxa, then Ranking Roger and Morton the drummer … they’re all gone,” he spits into the mic. “I just can’t get used to losing you,” he adds, cueing “Can’t Get Used to Losing You.”

If he still had a publicist, I imagine his face a ghostly white. Irony is something the lead singer and songwriter puts on in the morning like a buttoned-up shirt or the tie fastened to his stiff collar. His dry British attitude could cut through glass, with one set ending he’s off into another sardonic intro.

“The person who invented the espresso martini (Dick Bradsell) — honestly, I kid you not — is the same guy who gave me a fuck ton of lyrics on song two in the set (“Twist & Crawl“), went on to combine ice-cold coffee with ice-cold vodka,” projects Wakeling, working in the lyrics of “Twist & Crawl,” which appears on The Beat’s 1980 debut album, “I Just Can’t Stop It”.

Bradsell, a British bartender, had written poems, one of them adapted into song by Wakeling.

Like The Specials, but less punk, The English Beat came wrapped neatly in a bow placed on the top shelf. Originally “The Beat” they were signed under 2-Tone record label in late 1979. By the end of 1983, The English Beat was no more. Wakeling and Ranking Roger (vocalist) diverged into General Public with former members of their edgier cousins, The Specials.

Their catalog became the soundtrack to many coming-of-age dramedies (including mine). Movies such as “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off” (featuring “Rotating Heads”) or “Grosse Pointe Blank” (1997), where “Mirror in the Bathroom” overlays Hollywood’s first realistically shot fight scene — an acrobatic John Cusack somersaulting through his old high school hallways and killing his attacker with a fountain pen?

In some strange way, I shared the springhood of the crowd, yet I had not lived to see it. We had one thing in common: the music.

The English Beat, anyway, stumbled into my life one fall day during my junior year of high school, while driving the backroads of my hometown to my father’s apartment. “Save it for Later ” came on shuffle, bass drum kicking through the speakers of my car.

The satisfaction was something I had never encountered before — a rawness, yet lyrical melancholy, but mostly a place to put my sadness. It was nostalgia for a time I did not live, but also — hope — a dreamlike daze that everything would be alright. I played it every time I got in my car to each night when I danced alone in my room.

At the time, I didn’t fully understand the complexity of the lyrics in the way I do now. The effortless promise of your teenage years wasn’t going to carry into adulthood, nor would the era I was praying I’d make it to, be as simple as I thought. It became the soundtrack of my senior year, and Cusack’s fight scene — my physical anthem.

The track is relevant to me now more than ever, as I approach the other side of 21. What was really that bad at 17 (everything)? Wasn’t this once the very age I was waiting for, singing along for? And yet, I have nothing to show for it.

Wakeling himself once said, “It was about being lost, about not really knowing your role in the world, trying to find your place in the world.”

I found myself shuffling among others in the crowd, awkwardly attempting to find someone only moderately intoxicated to talk to. After approaching a brunette woman standing alone for an interview, she told me to wait for her husband and his friend to return. They were “The Beat specialists.”

Circling once again like a girl without a date at a school dance, I was waved over by the dark-haired woman, now accompanied by two tall, white-haired men: Michael Taubenheim and Christopher Schmit — spelled with a T (he assured me).

I questioned a towering Taubenheim if he was open to an interview, Schmit whispered confidently over my shoulder, “He’s shy.”

The longtime colleagues ribbed me about their not-so-budding friendship of the last 25 years. “The first 10 years, we didn’t talk to each other much. You can’t help who you work with,” Schmit taunted.

The pair works at Orcutt Junior High in Santa Maria, that night marking their third time seeing The English Beat — twice together.

The boozy banter went like this:

What is your connection to the band?

Taubenheim: “In high school, they were huge. I’m 56 now.”

Is there a certain song you are here for tonight?

He spouted syllables so fast, like keyboard slide and mumbo jumbo. I looked at him, puzzled.

He repeated, “‘Click Click,’ is my favorite song. It’s a real fast one, not one of the big ones. When I was a kid, it jacked me up ‘cause it was really fast.”

It was Schmit’s turn. He leaned into my mic, gripping it full handedly, attempting not to sway forward.

What’s your favorite song?

Schmit: “‘Mirror in the Bathroom’ — I think it may be about drugs, though.”

(A commonly misunderstood idea.)

“But only because my friend thinks the lyrics are ‘beer in the bathroom’,“ he sings, chuckling at his own joke, with the wit of a 15-year-old boy — the boy he’d resorted to during the set.

The song, originally written about Wakeling’s self-involvement turning into isolation, became an entire generation’s anthem for cocaine use on small handheld mirrors in bathroom stalls…

The “nose candy” jingle was ultimately inspired by a literal mirror in Wakelings’s sister’s bathroom in Birmingham, England.

After my encounter with the bromance duo, turned peanut gallery, I spotted two girls I thought could be around my age, dancing alone near the exit ramp: Mimi and Astrid, 19 and 23.

Astrid, a bass player who was also awaiting “Mirror in the Bathroom,” said, “I was playing the bassline the other day, and I thought it was really cool. I’m excited to hear them play it live.”

What made you come see “The English Beat”?

Astrid: “We used to listen to a bunch of ’80s music and ‘The Beat’ is one of the ones mixed in there. Mimi sent me an Instagram reel and I was like ‘we need to go to this’”

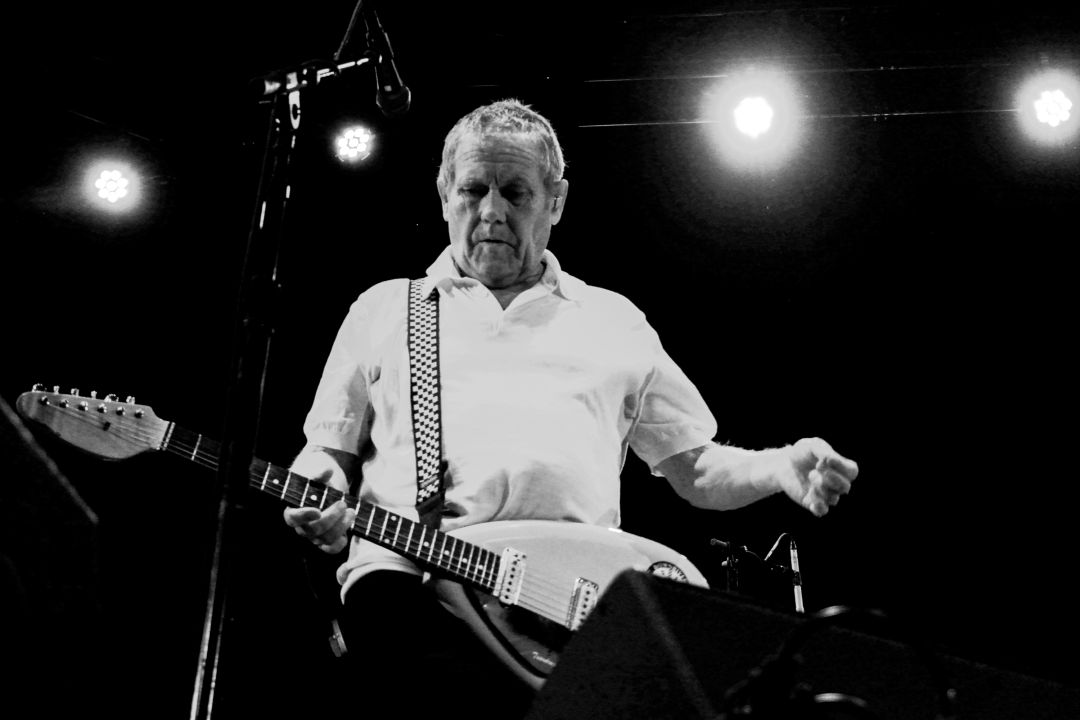

I conversed with music buffs across five generations and after advanced my way to the press pit. A monotone man in a shiny reflective vest motioned us inside with a head nod (the stamp of approval). To say I was excited was an understatement. I sat, knees pressed to my chest to take up as little of the grimy understage as possible. Under the barrier, I snapped photos on my gimmick Canon Power Shot A4000 — not professional by any means but it was something, mostly an excuse to see the band up close.

An animated woman, maybe in her late 60s, held up a “SKA” sign aggressively, shaking it over the divider. She attempted to get me to take a photo of her and once I did, it wasn’t an open-and-shut case — she wouldn’t stop.

After photographing the band up close and locking eyes with Wakeling — who grinned at me — press was escorted back to the pit. I had successfully made eye contact with the guy who wrote my favorite song of all time.

Somewhere between sticky floors and the first strum of Wakeling’s Vox Mark VI “Teardrop” guitar, we had already stepped through most of the setlist.

“Round and round the world for 45 years, you can’t introduce a song that many times. Some of them have been very odd years indeed,” Wakeling said.

He cued the night was coming to an end, but the song I had been hoping for was about to begin.

The room held its breath as Wakeling’s backing band hyped up the crowd. A familiar riff filled my head and I smiled, embarrassingly teary-eyed.

Men and women, young and old, were dancing to dance. Acting plainly like children, the softness of music allowed the crowd to indulge in nostalgia. A circle of moshing adults formed — complete with balding, bearded men to salt-and-pepper-haired older women. Younger concertgoers hopped in and out, and a worming dude with messy hair took the center. The feeling of their youth was back in town — literally and figuratively.

“We can have anything we want, except we can’t have the past.”

My chest suddenly felt hollow … a statement that gutted me from the outside in. I couldn’t have my teenage years back and neither could Taubenheim and Schmit, (they had already come to this realization long ago).

Funny — This is the closest thing we could hold but not have. As if Wakeling hadn’t just said the most heart-wrenching declaration, the lights went out.