Native American poetry and its portrayal of Indigenous reality

The following article references sexual assault and violence. Cal Poly offers prevention education and confidential advocacy through Safer, which can be found at safer.calpoly.edu.

Native American poetry brings forth a perspective that is completely unique in its existence and exponentially valuable in its insights. Centering around the reality of being an Indigenous individual in America, Native American poets explore the harsh realities and, at times, the devastation of their culture, land and identities in this country as a result of colonization.

Reading Indigenous poetry is a powerful way to learn about and bring awareness to the reality of the effects of colonization on Indigenous people. Education by way of consuming art allows us to emotionally immerse ourselves in the experience of the artist and provides a genuine insight into a way of life and thinking.

The following five Indigenous poets are representatives of a literary tradition that is much richer and more widespread than the six poems mentioned in this article.

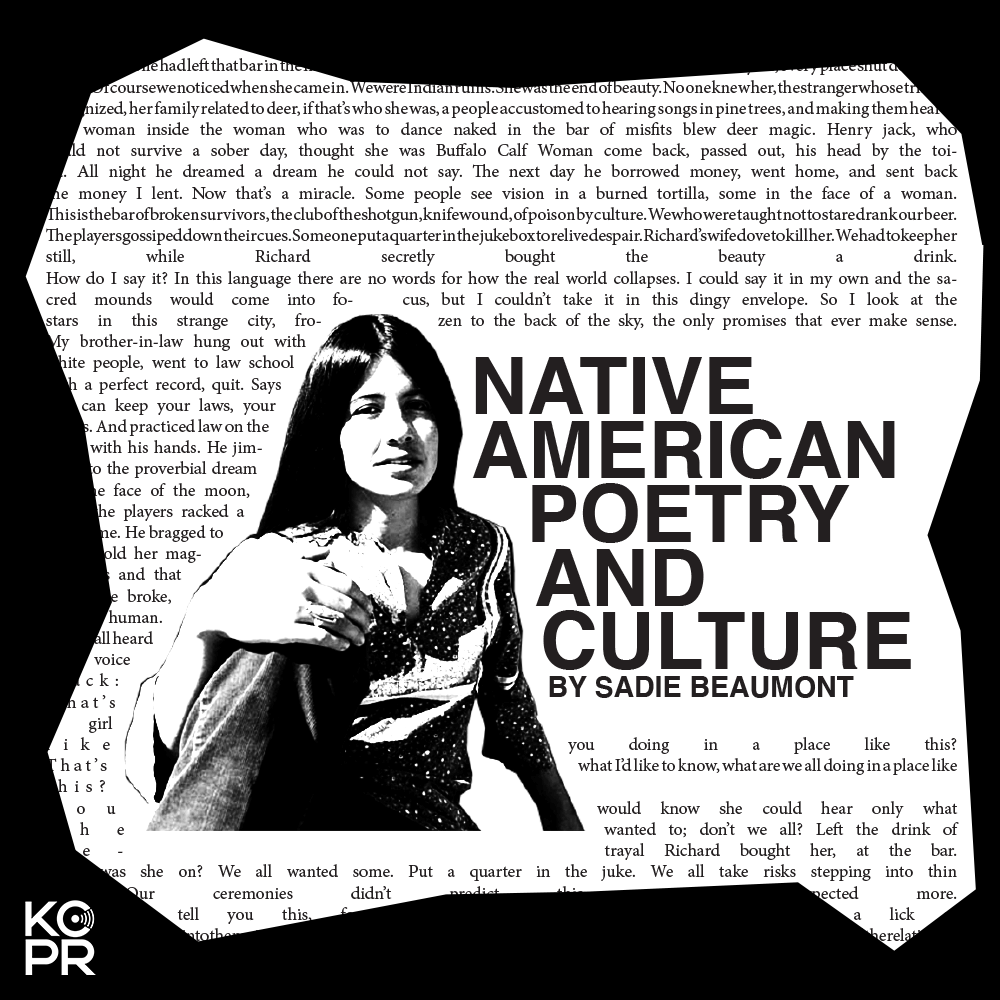

Joy Harjo recently completed her third term as the 23rd Poet Laureate of the United States. From Tulsa, Oklahoma, Harjo is part of the Muscogee Creek Nation and received Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in creative writing.

Native American poetry offers an often sobering viewpoint into Indigenous culture in relation to settler culture. The effects of colonization linger not only on reservation land, but also in the hearts and minds of its people.

Joy Harjo’s “The Path to the Milky Way Leads through Los Angeles” estranges the reader from the reality of Los Angeles. Looking through the eyes of an Indigenous person trying to live in one of the biggest cities in America, the reader comes to understand a forced existence in alien culture.

Harjo also emphasizes the total loss of any ties to nature when she describes how “we can’t easily see that starry road from the perspective of the crossing of boulevards […] but we can buy a map here of the stars’ homes.”

This distancing from the natural world’s prevalence in American culture is a motif in Harjo’s work.

Towards the end of the poem, the speaker asks Crow, who is traditionally a symbol of wisdom in Native American culture, what to do. While Crow tells the narrator to “wait and see,” it seems as though, for an Indigenous person, a clear purpose does not seem to exist in Los Angeles.

Indigenous poets regularly explore the effects of colonization.

Joy Harjo’s “Deer Dancer” depicts a bar scene on a reservation. It illustrates the reactions of the regulars when a woman from “a tribe we recognized, her family related to deer” enters the establishment. The chaos that follows references many effects that colonization has had on native people.

Placing the scene in a bar is representative of the high rate of alcoholism seen in Native Americans. Harjo describes the bar regulars as “broken survivors, the club of the shotgun, knife wound, of poison by culture.”

Indigenous Americans “are 2.5 times more likely to experience violent crimes and two times more likely to experience rape or sexual violence than any other race,” according to the Association on American Indian Affairs.

In the poem, the woman takes off her clothes and dances naked on the table. Turning to sex work, being fetishized by American culture and being subject to uninvestigated rape, abduction and murder cases are all part of the reality of colonization and its effects on Indigenous women. Joy Harjo’s ability to effortlessly weave these harrowing statistics into a narrative that seems mundane and normal offers a stark insight into the many effects of colonization.

Jake Skeets is a multiple award-winning poet from the Navajo Nation. He attended the Institute of American Indian Arts, where he got his MFA in poetry.

Indigenous poets, like Skeets, depict the in-between experience of belonging to multiple ethnicities. Authors might also express their struggles with imposter syndrome, feeling as though they do not truly embody their culture or customs well enough. Indigenous American poets often write about the hybridization of Indigenous heritage and American features, which can lead to their cultures, identities and languages embodying this in-between experience.

Skeets’ “Learning about Treaties in School” depicts and physically represents the in-between experience of Indigenous people in America, contrasting scenes of American teenage life with lines from the Navajo Nation Treaty of 1868. Such a contrast indicates that these boys do not fit in at an American school nor are they wholly representative of the Indigenous people in the Navajo treaty. Instead, they are best represented by a hybrid poem of both.

“ARTICLE 13. A lesson on permanence. / like water?” suggests there is no permanence when it comes to the Indigenous in-between identities and they instead move fluidly between both, like water.

Louise Erdrich is a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians in North Dakota. In addition to her poems, Erdrich has written award-winning novels, short stories and children’s books. She received her Master’s degree at John Hopkins University and became a resident writer at Dartmouth.

Traditional Native American poetry was passed down orally, and the linguistic hybridization with which traditional stories were told still remains. Louise Erdrich’s “I Was Sleeping Where the Black Oaks Move” includes both Erdrich’s memory of a flood destroying the forest around her home and the story passed on by her grandfather. As Erdrich watches the herons displaced by the flood and searching for shelter, her grandfather says “These are the ghosts of the tree people / moving among us, unable to take their rest.”

With this fable, Erdrich’s final stanza is able to take on a new meaning, turning the flood into an allegory for the forced colonization of Native Americans by white settlers: “How long must we live in the broken figures / their necks make, narrowing the sky.” Like the ghosts of the tree people, Indigenous Americans are no longer able to find rest in what once was their home.

Leslie Marmon Silko is of Laguna Pueblo, Mexican and Anglo-American heritage. She grew up on the edge of the Laguna Pueblo reservation and went to school on the reservation until the fifth grade. She has earned many awards for her poetry, including a Pushcart Prize for Poetry and the MacArthur “Genius” Award.

One of the many ways Indigenous poets incorporate their culture and heritage into their writing is through the use of the Coyote story. Coyote is a recurring character in Native American myths, and can also be represented as a crow. Coyote is a trickster, never fully good or fully evil, and has the powers of resurrection, medicine and transformation. Sometimes Coyote will act nobly, but dangerous and cruel at others. These coyote stories are told as forms of entertainment, but can also be cautionary or instructive tales.

Silko’s “Toe’osh: A Laguna Coyote Story” emulates both. The third stanza details a mischievous coyote cheating at a contest to win a prize. As the poem goes on, Silko grows more serious, depicting the Indigenous peoples’ struggle to keep their own land, corrupt white governors and the fraught relationship between colonizer and colonized. Silko uses the coyote figure throughout to detail how, at times, Indigenous people were able to trick and outsmart white settlers — becoming the Coyote — while at other times, they were the ones being outsmarted.

Sherman Alexie is a Spokane/Coeur d’Alene tribal member, poet, filmmaker, novelist and performer. He grew up on the Spokane Indian Reservation in Wellpinit, Washington. He found success after his first publication in a magazine, which inspired him to quit drinking, and he has remained sober ever since.

The reality of reservation life and how many reservations are systematically kept in poverty is a recurring theme in Indigenous poetry. Native American land has historically been viewed as a free resource for white colonizers. Alexie’s “Evolution” is a short, but sobering glimpse into shameless white exploitation of Indigenous people, their belongings and their land:

Buffalo Bill opens a pawn shop on the reservation

right across the border from the liquor store and he stays open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week

and the Indians come running in with jewelry

television sets, a VCR, a full-length beaded buckskin outfit

it took Inez Muse 12 years to finish. Buffalo Bill

takes everything the Indians have to offer, keeps it

all catalogued and filed in a storage room. The Indians

pawn their hands, saving the thumbs for last, they pawn

their skeletons, falling endlessly from the skin

and when the last Indian has pawned everything

but his heart, Buffalo Bill takes that for twenty bucks

closes up the pawn shop, paints a new sign over the old

calls his venture THE MUSEUM OF NATIVE AMERICAN CULTURES

charges the Indians five bucks a head to enter.

Courtesy jenksps.org

The work of these five poets has served to further richen the tradition of Native American poetry, and there are so many other Indigenous authors to discover. Reading more Native American poetry and exploring the works of other authors is an invaluable resource for first-person knowledge and insight into Indigenous American culture.