Can We Separate Art from Artist?

Recently, a six part documentary on Lifetime investigating and illuminating the allegations of R. Kelly was released.

The series, “Surviving R. Kelly,” includes the testimonies of several women subject to his abuse.

These testimonies reveal, among other things, the degree of criminal activity R. Kelly has committed and gotten away with. In both 1996 and 2001, Kelly was accused of having sex with teenagers. Following these, in 2002, a video was released that depicted Kelly having sex with a teenage girl and urinating on her. One year later, his album “Chocolate Factory” would go platinum. In the next four years, four more of his albums would also go platinum.

He has yet to be found guilty by any judge or jury.

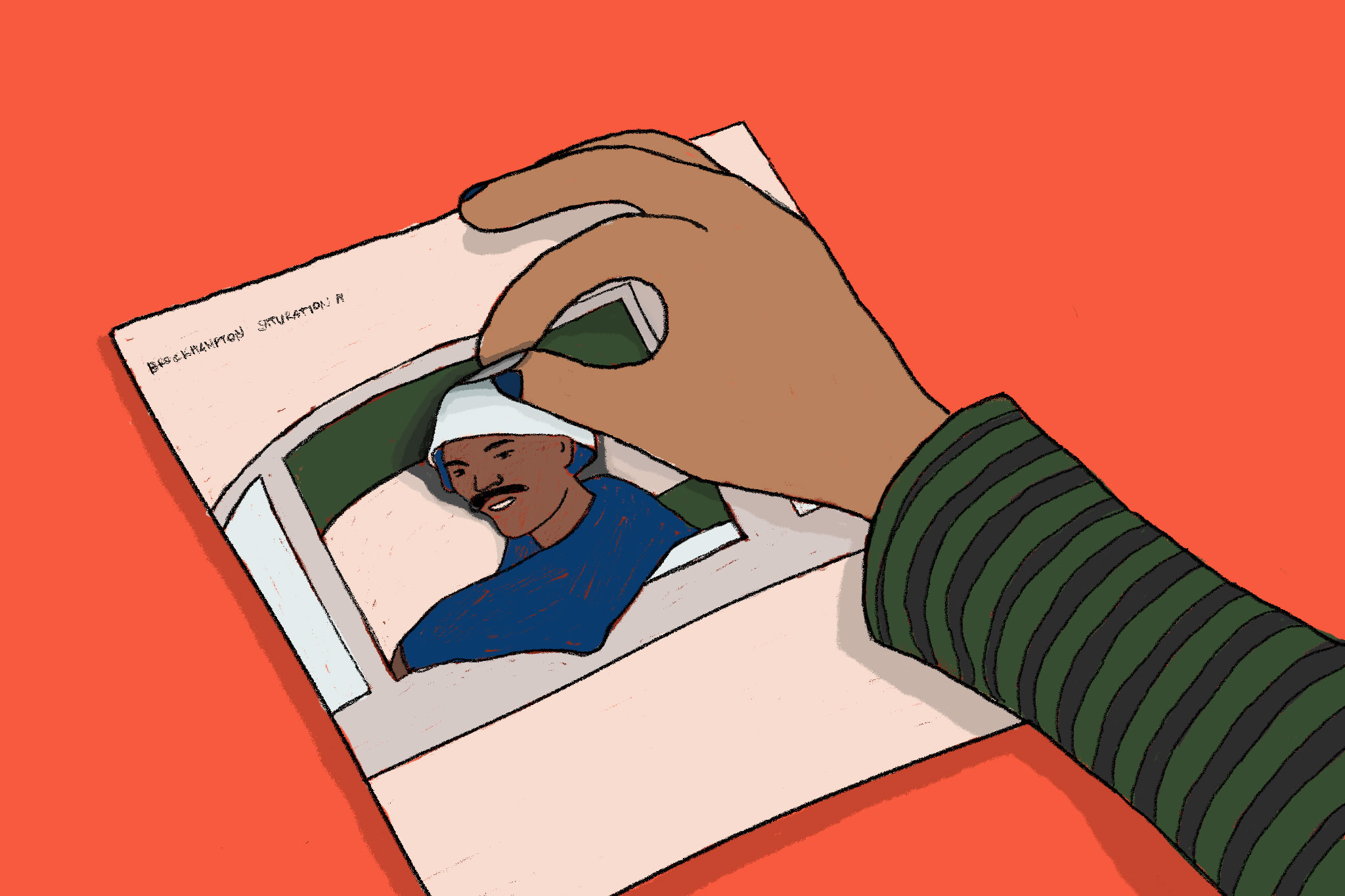

R. Kelly is merely one example of the music industry’s lack of justice. There is an exhaustive list of artists who, in light of recent accusations, have been exposed as perpetrators of sexual misconduct. Many of them, like R. Kelly, have managed to stay within the popular public lens. From indie rock band Foxygen to pop-rap group Brockhampton, this list extends throughout all genres, imbuing our entire music culture with an epidemic of unacceptable behavior.

Unfortunately, Hollywood often acts as an inadvertent patron for sexual misconduct. By nature, the platform of fame gives many artists a means to embody the character of a sexual predator without its usual penance. With commercial fame comes influence, and with this influence, it seems, comes the capability of harming others.

How do we, as individuals, prevent this from happening?

An ideal answer would be to completely stop listening and participating in art created by these problematic artists. Yet this is difficult to enact. The number of artists who’ve committed inexcusable acts extends disappointingly far. There is, to some, a solution — we separate the artist from their art. The question that arises from this is — is such a thing possible?

Music can mean many different things to different people. Some might argue that the interpretative nature of art can allow listeners to listen to music objectively, without connecting with the artist themself. One person can look at a piece of art and see something entirely unlike another’s. We see what we’ve experienced as individuals, and the words written in by the artist themself are merely a vessel for our own introspective understanding. In essence, the meaning of art is dependent solely on the way it’s interpreted by its audience. The artist has nothing to do with it.

Further, many believe our analytical lenses should lie purely within the work itself. Who cares who created it? The art alone is what matters. We shouldn’t discriminate art based on the artist’s race, gender identity, or sexual orientation.

Yet here’s where completely ignoring the artist gets tricky. Basing art solely on its content, without allowing context to dictate interpretation, is a near hopeless feat. Art is so much embedded within our culture that placing any work in an elevated space, secluded from the vices of society, is impossible. Raising it up to some far-off pedestal is contradictory to art’s very essence. Art allows people to express themselves, and the expression cannot exist without the artist.

Further, an individual’s art can provide a very intimate look at who they truly are. Recently, rapper Ameer Vann was kicked out of rap group Brockhampton due to an abundance of sexual misconduct allegations. Singer-songwriter Rhett Rowan, among others, claimed that Vann was emotionally abusive and would have sex with underage fans. This leads us to the inevitable question — can we separate his actions from his art?

The problem is, artists don’t separate themselves from their art when they create it. Many rappers, for example, rely on their background as a source for their creative genius. Their livelihood is reflected in their art. Authenticity is priority, and if anyone were to question a rapper’s experiences or environment they grew up in, the accusation would not go unnoticed.

In Kevin Abstract’s song “Silent Water,” featured Vann paints a complex portrait of his history with drugs and addiction, a struggle that is directly transposed from his past experiences. Throughout his life Vann has wrestled with addiction issues, and, if one were to remove this background from the song, he would lose his legitimacy. To place a disconnect between Vann and his music would be arguing against his own authenticity. Since Vann’s livelihood is very much imbued within his art, successfully isolating the two would prove impossible without also declaring his art baseless. If arguing for a disconnect implies arguing against the validity of an artist’s experiences, then the act of doing so would create all sorts of illegitimacy throughout music culture.

In addition, a large majority of artists lend their fame to the celebrity characters they create for themselves. These distinct personas portrayed onstage are as much a reflection of themselves as their art is, and they often spend just as much time curating their pop identity as they do creating music. David Bowie, along with his alter ego, Ziggy Stardust, and Lady Gaga, whose outrageous fashion garnered a distinctive fanbase, are just two examples of a long list of artists who’ve crafted images for themselves in tandem with their music. This further blurs the line between the artist and the art, and, in many cases, the distinction disappears almost completely. The resulting product is a hazy cloud of ambiguous identity. The inventor becomes the invention; the creator their creation (and vice versa).

Bowie is a perfect example of someone who has taken their music and molded it into something that transcends mediums. Throughout his career, he has fashioned a network of art surrounding his persona, establishing himself as a noteworthy figure, a character both derived and designed.

His music itself has been praised for generations, and I, as well as many others, have looked up to his lyrical expertise and melodic talent. So when we all found out he’d devirginized a 15 year old in the ‘70s, the notion of separating him from his art became incredibly enticing. Yet Bowie’s music is nothing without him. The genius that struck passion and admiration in our hearts did so through a multifaceted medium. It wasn’t merely the catchy melodies of “Moonage Daydream” or “Suffragette City” that made us stand up and give applause, but the omnisexual alien rockstar that was Bowie — striking makeup, painted face, gender-bending outfits and all.

The fact that you can be brilliant, beautiful, and ingenious and also like underage sex is, for some, a hard truth to grasp, but a truth nonetheless.

It’s also a truth we must attend to. Bowie isn’t the only role model that’s revealed to have been less than perfect. Celebrities are admired by many, even those who’ve given us much reason against the fact. If we continue to give a platform to artists whose values seem questionable, we provide problematic role models for future generations, further perpetuating the systematic compliance toward sexual misconduct. If we listen to abusers and rapists, we suggest our own moral ambiguity. As individuals, we need an ethical lens to make judgements through, and if we can’t stay consistent with this lens, how can we say we have a moral compass?

Further, what we choose to listen to has material implications — by listening to R. Kelly we are funding his misdemeanors and enabling his and others sexual misconduct — and even if there isn’t a tangible transaction occurring, by listening to these problematic artists we are forwarding the mindset of acceptance and acquiescence. This not only preserves its unhindered occurrence, but also prevents chances for the victims to attain credence in society. The more we give ground to the perpetrators, the more difficult it is for victims to speak up.

There is no way for us to create a collective moral standard, wherein we draw lines between ethically “good” and “bad” artists. Creating a universal set of criterion to determine such a thing is impossible. However, on an individual scale, it’s important to acknowledge where we’re experiencing cognitive dissonance and make a decision on how to act. The philosophy of separating an artist from their art crumbles when placed under scrutiny, so perhaps it’s time we weed through our perspective music tastes and pull out problematic artists like R. Kelly and Ameer Vann. If sexual assault, domestic abuse, and other sexual misconduct become the poster child of celebrity status then we, as supporters of the music industry, have failed. I hope that, as a powerful next generation, we can seize the future by its oxford collar and alter the fixed mindset of the music industry.

The masscult is stubbornly resolute, but not infallible. All we have to do is prove it.

Ethan Hundertmark is a Cal Poly English sophomore and a KCPR staff member. He wrote the article. Ally Millard is a Cal Poly art & design senior. She created the illustration.