GOLDEN GATE STATE PARK, Oct. 4 — High above the crowds, golden, diffused light danced through the Oak and Monterey Cypress trees, swathing us –– the friends, the families, the lovers, the locals, visitors, dreamers –– in a unifying glow.

The festival grounds were buzzing with the energy of half a million attendees, and people from all walks of life were moving through their day in closer proximity to one another than daily routines typically afford. It was Saturday afternoon; day two of Hardly Strictly Bluegrass –– an uniquely San Franciscan experience.

Around the six stages throughout the park’s 1,000-some acres, where 80 acts were set to play, tapestries of vibrant lawn blankets with the scattered belongings of perfect strangers overlapped with one another at the corners, creating an interwoven mosaic on the lush green grass.

Singer-songwriter Patty Griffin –– a frequent performer of the festival –– had just rounded out her set on one of the main stages, and a hundred paces away, another crowd the size of a football field was moving about like ants, claiming territory near the stage, chatting with one another, and idly awaiting the Cuban musician Cimafunk’s arrival.

It was electric to be around so many people.

For a moment, I stepped away from my friends, becoming a silent observer. I admired families eating elaborate lunches together, and kids chasing each other, weaving through the masses. Others were fiddling with toys, contorting their Barbies’ limbs or careening monster trucks across the day’s bluebird sky. Newborns lay cradled in parents’ arms, their heads swallowed by giant headphones, and leashed dogs received pets from outstretched arms, leading to sparked conversations between owners and animal-lovers.

Hackysacks were passed from foot to foot in huddled circles like hot coals, and in minutes, strangers joined in and transformed quite instantly into new friends. The old and the young were rocking flowy skirts and tie-die shirts; bandanas and cowboy hats; stylish boots and muddied bare feet. We moved through the hours together.

Cimafunk needed no introduction, as his unique blend of Afro-beat, funk, and Latin rock lured his growing audience up from their seats and into an addictive rhythm of movement. Dimples and creased mouth lines appeared on some through laughter, and beads of sweat on the foreheads of others gave such youth to those who danced and swayed to the music.

It was free, after all, as it has always been.

Since its beginnings 25 years ago, Hardly Strictly Bluegrass has held onto its core foundations, keeping the inclusivity of free music and a supporting community at the heart of the annual festival. That was what the SF philanthropist and private equity investor Warren Hellman intended when he funded the festival in 2001.

Known for his civic engagement and steadfast reverence for community arts, Hellman––a banjo player and music-lover himself–– once coined the festival a selfish gift that all could enjoy, and questioned what money was for if not for something like Hardly Strictly. He died in 2011 and left an endowment to continue funding the bluegrass festivities.

The festival has grown from one day to three, and in 2004, ‘Hardly’ was added to the name to encompass the bluegrass-adjacent genres. In 2005, Doc Watson, Dolly Parton, and Joan Baez were among the lineup; in 2008, Robert Plant graced the stage, and in 2012, Gillian Welch, among many.

This year’s audiences welcomed back folk and country rock artist Emmylou Harris, who has amassed 14 Grammys throughout her 40-year career and has remained a symbol of sorts for the festival, having performed every year since its genesis in 2001. Other festival staples who returned once again included Chuck Prophet and His Cumbia Shoes, along with Steve Earle and Moon Alice.

Mixed in with the older musicians seeped in the past were newer artists and bands like R&B and soul group The Altons, Montana-raised folk band Tophouse, and indie pop duo Hovvdy.

An early October tradition

For many Hardly Strictly fanatics, there’s no other way to spend the first weekend of October each year.

College kids from around the state pack into cars with their phones mapped for the park; SF-natives make their familiar commutes through the heart of their city; and for Bob and Anne McNaughton of Scotland, plane tickets are booked long in advance, in anticipation of an experience they deem like no other.

They hail from Perthshire, also known as the “Gateway to the Highlands”, they told me, as I joined them on their spot on the grass. Flapping in the light wind behind them was the blue and white Scottish Saltire flag, fastened across the backs of their camp chairs.

Every year they fly to San Francisco, they said, and this year they were looking forward to embarking on a larger road trip after the festival –– driving to San Antonio, Texas for the Austin F1 Grand Prix race in mid-October, then heading home.

It was in 2013 when the couple first stumbled upon Hardly Strictly, in a manner as spontaneous and unfettered as the festival is.

“The first time we came, we had driven Route 66,” Anne said. “[Bob] Googles live music wherever we go, and coming up the PCH, we found Hardly Strictly Bluegrass.”

They went that Saturday, and decided on the spot they would return the following year, and the year after that … and the year after that.

It’s a lot busier than it was 10 years ago, they both agreed, though noted the vibe of the festival has not strayed from its early roots.

“It’s always peaceful,” Anne said. “We’ve never seen any trouble; it’s always trouble-free compared to some festivals. San Francisco has a certain vibe that other cities don’t have.”

After a few-year hiatus from traveling to America, the two are now retired and have more time –– and willingness to dip into the pension pot, Anne said with a smile –– to make it back to the city each year again. The atmosphere is what keeps them coming back, and the youthful yet nostalgic energy of the festival makes for a relaxing three days.

Anne and Bob enjoyed the gravelly soul voice of Nashville-based artist Anderson East, who they saw perform in 2015, and reveled in their chance to see the infamous British guitarist Albert Lee, who has played in their Perthshire hometown numerous times.

Dancing to Jason Wilbur and Dave Jaques perform the timeless hits by John Prine at a stage a minute’s walk away, Natlya Crawford twirled and sang arm-in-arm with her friends. They appeared so enveloped in their group and the surrounding festival-goers, and as Wilbur and Jaques left the stage to make room for Lucinda Williams’ set, I learned that Crawford, who is from Vallejo but currently lives in the East Bay, has made it a goal to get to the festival every year for the last five years.

As a high schooler, she wasn’t convinced this would be her scene, but said she realized she really enjoys the music –– both the big-name headliners she’s seen in past years, like Kurt Vile, M. Ward, and Thee Sacred Souls, and the acts performing on smaller stages.

“It’s also my favorite thing to do, to find somebody I wouldn’t have particularly listened to before,” she said. There’s a particular joy in hearing new artists play live and immediately becoming a fan, we both agreed.

“And because it’s free, you see so many different kinds of people,” she added.

Other festivals, like Outside Lands or Lollapalooza, with extremely high ticket prices, are curtailed only to the people who can afford them. And many times, as Crawford noted, people don’t sit and sprawl like those that make up the Hardly Strictly landscape do –– setting up shop on the grass and picnicking for hours.

Our light-hearted conversation fizzled out as Lucinda Williams made her way slowly to the middle of the stage. Before I rose from my seat and started to dance, I couldn’t help noticing the tattooed calf of a man standing in front of me. Underneath a blue guitar tat and the Rolling Stones Union Jack tongue icon, his leg read: Lucinda Williams, in a striking red ink. I couldn’t help but tap on his shoulder.

‘I like your tattoo,” I said unabashedly. “You must be ready for this.”

“I was ready a decade ago,” he replied with a wink.

And just like that, Lucinda, the 71-year-old pioneering Americana, folk artist who is still recovering from a stroke in 2020, held nothing back as she sang her classic tracks “Fruits of My Labor” and “Car Wheels on a Gravel Road” to fans.

Between her greatest hits, she sang with equal passion her 2020 track “Stolen Moments”, which she wrote and dedicated to Tom Petty following his death, along with the infamous Bob Marley and The Wailers song, “So Much Trouble in the World”.

“This one is dedicated to all y’all, all of us,” Williams preached into the microphone, and soon we all softly hummed the lyrics with her.

Repeating the line “so much trouble in the world” felt oddly comforting and equally saddening; having been written by Marley over 40 years ago regarding conflict, inequality, poverty and environmental issues, each line felt just as relevant.

Williams left us with a cover of Neil Young’s 1989 hit “Rockin’ in the Free World”, and with a building tempo and irresistible chorus, the crowd held nothing back in creating an anthem of sorts that reverberated through the trees.

Moving with the music

Hours folded into hours, and with phones feeling trivial in an atmosphere like this, it was the sun sweeping overhead that gave me a sense of time.

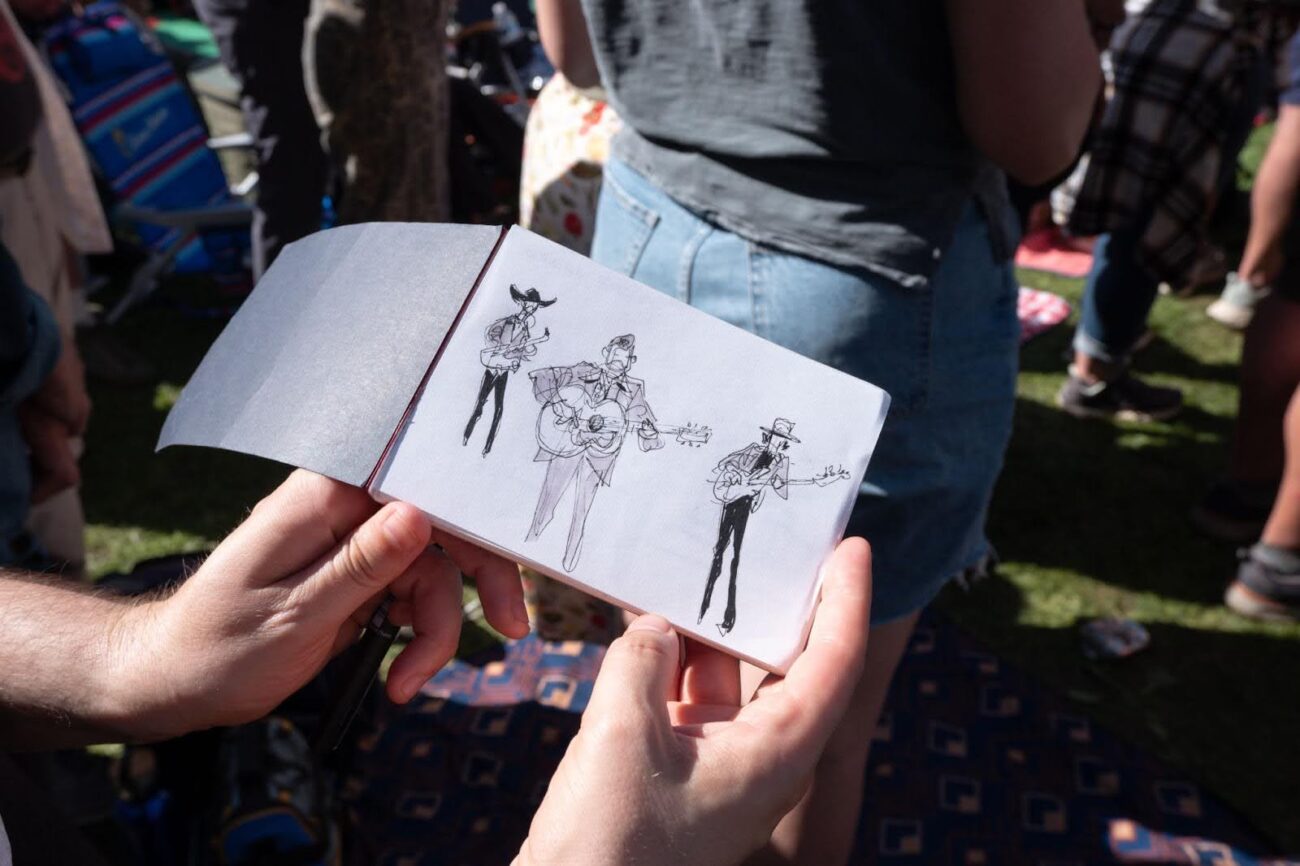

Swimming through another crowd of smiling faces, I came upon a man with his head down at his feet –– a stark contrast to the masses around him whose eyes were stuck to the stage. With two pens in hand and a small notebook in his grip, its edges worn by good use, he focused intently at his drawing, occasionally glancing upwards to piece together the musicians and instruments.

I didn’t catch his name, but he said he was an artist by trade. New details were added as each song was played, and the slowly actualizing snapshot of the band was titled and tucked back into the notebook and into his pocket. What a beautiful way to experience and remember a festival, I thought to myself.

One performance led to the next, and in the hazy interim when folks filled the dirt footpaths and meandered every which way, the people watching really began.

Hard to miss was the poet Stan Vilensky of New Orleans, clacking away on his Royal typewriter, deep in the personable and spontaneous act of writing a poem for a stranger. He works with a word or short story given to him by those who are interested, and cranks out lines of verse.

I caught the eye of another poet, pulling behind him a makeshift cart with a patchwork sheet draped over it, that read: POEMS.

And under a shady grove of low-hanging eucalyptus, a vintage portrait photographer who soon introduced himself as Richard Barnitz was disassembling his 1906 large format homemade box Conley camera.

His latest images –– rich black and white snapshots of festival goers –– were still soaking in chemicals in a bowl near his setup, having just been developed in-camera.

“You look wonderful,” he said, greeting me with the same warm smile he afforded to his earlier portrait subjects. “It’s a shame, you would have made a great picture,” he added, before I noticed the uniformed cops congregating next to his station.

They were making him take everything down, something to do with his permit, he told me. But he quickly showed me the inner workings of his prized possession, which he proudly declared he built himself, having bought various parts off eBay. A business card was placed in my palm, if I ever tracked him down again.

His business, Farm to Frames, offers services for weddings and events around Santa Barbara and Oakland. Oh the people you meet, I mused.

A short stroll away, I singled out the raspy twang of Jeff Tweedy’s voice mingling with the applause from Americana musician Buddy Miller’s audience at another stage. There was no right or wrong plan for the weekend; it felt like music and life were nestled in every corner of the park, inviting you to dip into anything that called.

I had come upon a more modest stage, coined Horseshoe Hill, where hours prior I had caught the tail end of Grenadian-Canadian singer-songwriter Kaia Kater’s set. The stage was transformed into what appeared to be a Victorian-style living room, with worn-out picture frames hanging over floral wallpaper, and a bricked-up fireplace.

Squished in the cozy backdrop was Kater, along with two musicians playing a double bass and a fiddle. Most of their audience was seated, packed tightly next to one another.

It was almost sundown, and the Australian singer-songwriter Courtney Barnett was soon to perform. Her distinguishable, deadpan sound concluded day two, and set us loose for the night, like the shutting of a novel at bedtime sends one into dreams. The ethereal lyrics of her 2015 track “Depreston” replayed in my head as I exited the park.

Helper in promoting peaceful individual existence

Hardly Strictly feels as close as I can get to the past. The weekend of play among the trees and dirt appeases my wistful longing to have been young in the hippie era of the 1960s and early ‘70s counterculture movement –– to have embodied the notions of peace, love, and freedom with my entire being in an undigitized culture.

“Every generation has its hippies,” Anthony Martinelli had reassured me when I asked the 71-year-old donning a sleeveless purple and white tie-dye 2010 festival shirt, if he thinks Hardly Strictly has morphed over the 25 years.

“Not changed one bit,” he told me with a smile, his face downturned to meet my eyes.

Minutes before our full-fledged conversation –– where we revealed random pieces of ourselves through memories of childhood and found common ground through an undeniable love for live music –– we were strangers sitting side-by-side on the lawn of Swan Stage.

He told me he’s been to Hardly Strictly every year, and with that, the conversation sprang.

“The free music has always been about this park. When I was a young teenager, I came to the free concerts to panhandle, and ended up working for Bill Graham,” he chuckled. “I injected myself into the music scene.”

In 1998, Martinelli was homeless and living in Golden Gate State Park. “When Hardly Strictly Bluegrass started while I was living [here], I was like ‘Are you kidding me?’” Years in different states and the Air Force brought him full circle, living in a nice apartment back in the city he grew up in.

His enthusiasm grew, like he’d been waiting to speak of the festival’s magic to someone for a while.

“It’s the fact that they bring in everyone from Alice and Kraus and Robert Plant, to The Avett Brothers and acts on the small stages where there are poets you’ve never heard of who invite you to sit and be captivated,” he said.

“People should come out and listen to all the music they can get, especially the free music, because there is so much everywhere being shared.” He’s tried Outside Lands –– once, he said –– but there’s something undeniably special about festivals like Hardly Strictly, or the Anniversaries of the Summer of Love concerts also held in San Francisco.

“Look out at all these oldsters like me around,” he said. “I’ll be 72 next month, and I’m just like a big kid.”

And with that sound roared from the loudspeakers and another performer appeared onstage. Our conversation ended –– at least the chatter. But really, as we swayed and smiled and embodied the freeing nature of good music in a city buzzing with life, our conversation had only just begun.

‘Til next year

As Sunday evening crept in, Andrew Marlin and Emily Frantz, the North Carolina-based duo of Watchouse, played the crowd into a trance. Eyes were shut; bodies sought out one another.

Love took center stage. Fitting, since the couple has been married for over 15 years.

There was such youth and purity to the interplay between Marlin and Frantz –– both multi-instrumentalists who swapped from song to song, guitars for banjos, mandolins for fiddles, and lyrics for the crowd’s collective voice.

Tracks from their most recent album, “Rituals”, released in May, dovetailed into fan favorites like “Old Ties and Companions” and “Wildfire”. Bobbing in and out of my own world, where old memories welded together by Watchouse songs floated in and out of my mind, it became apparent how each track represents something deeply personal for every listener.

This thought led to the next: We are all the same here, and oh, how connected.

Situated on the lawn awaiting Watchouse’s arrival onstage, an older man in the middle of the sprawled crowd attempted to step over the legs of hundreds before him. As we saw his eyes scan where to go, everyone immediately paved a path for him, outstretched hands for him to steady himself as he tiptoed through criss-crossed legs and strewn belongings.

“Oh my God,” he exclaimed as he neared closer to me and grabbed hold of my hand. “Everyone is so nice here.”

Later as I swayed arm-in-arm with my boyfriend to “All Around You”, a middle-aged woman turned around and locked eyes with us, then, without as much as a thought, whipped out her Polaroid, turning her back to the stage once more to face us and snap a photo.

“Here,” she said, shoving it face down into my pocket. “Hide it from the light for a few minutes,” she explained, leaning in for a hug before turning back to be with her family.

When Watchhouse disappeared offstage, marking the end of this year’s festival, most hung around as if slowly waking up from the trance we’d fallen under.

Before our impromptu Polaroid photographer left, she circled back to us.

Someone had done a similar thing to her at a Burning Man Festival when she was younger, she said, and the act of selflessly memorializing her in a photo and immediately gifting it to her afterward changed her life.

I took it as she meant that person had made her feel seen.

With that, I retraced my earlier steps along the dirt paths with my beloved friends, crossing the giant lawns into the trees and out to the city where the full moon peeked from behind the street-lined houses. Goodbye to the festival that makes me feel seen, I thought, until next year.