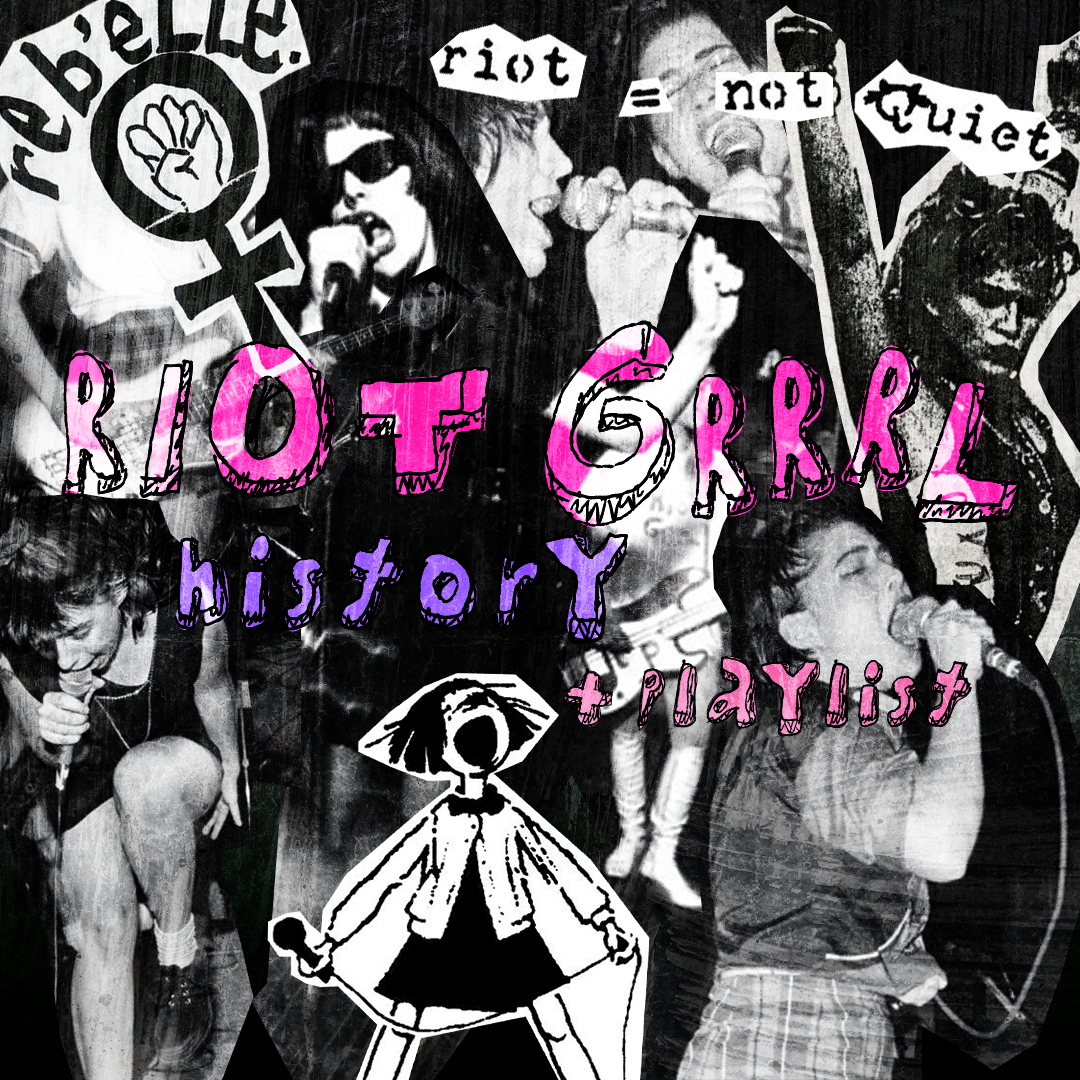

“We’re Bikini Kill and we want a revolution:” Riot Grrrl deep dive

“We’re Bikini Kill and we want revolution / Girl-style now” boomed through the punk scene in 1991, declaring war on hypermasculinity, with the release of “Double Dare Ya” by Bikini Kill. This is just one of many Riot Grrrl anthems.

What is Riot Grrrl? Is it a movement? A genre? The name itself is highly debated and yet remains highly relevant to womxn within the punk scene today.

Emerging in the early 1990s, a group of women in Olympia, Washington, met to address a collective experience with rampant sexism, harassment and exclusion within the punk scene, according to the director of the Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality at the University of Chicago Kristen Schilt.

Following the meeting, Riot Grrrl began to spread and grow important within feminist and punk communities across the United States. A network of activist chapters was formed to organize protests, performances and meetings for members to raise awareness about the growing sexism within the punk scene, according to The New York Times.

Riot Grrrl quickly grew into a movement unlike any other. Performative shock factors and uncensored art developed a new lens of unfiltered feminism, along with a new subgenre of music that combined politics and punk rock. With witty slogans such as “girl power” and “support girl love,” along with protests and politically motivated art, Riot Grrrl could be seen as third-wave feminism, as stated by The New York Times.

It merged the “girly” side of feminine qualities with the loud, chaotic and reckless side of womxn, which is particularly seen in performances and music from original Riot Grrrl bands like Bratmobile, Bikini Kill and Le Tigre.

Kathleen Hanna and Tobi Vail, members of Bikini Kill, produced one of the earliest fanzines associated with the movement in 1991. It contained a Riot Grrrl manifesto declaring the movement’s necessity, according to Schilt.

These self-published and non-commercial printed works, most commonly referred to as “zines,” became prevalent in the late 1970s, allowing white men to produce and curate their own content untouched by capitalist hands. Riot Grrrl, however, shifted zines to become a medium of discussion on more taboo topics related to female experiences and struggles in the ‘90s.

Zines served (and continue to serve) as powerful outlets for content that was oftentimes considered “too niche” for traditional publication, according to The Bindery.

“I liked certain bands — Bratmobile, Bikini Kill — and I just really connected with how loud and angry these girls were,” art and design sophomore Isa Cordovez said. “And then I saw their album artwork and checked out their zines, and I loved how while being so angry, feminist and unapologetic, they were also girly and playful. People, a lot of the time, think you can’t be both.”

Zines offered girls a way to form connections and discuss the marginalization they felt in a predominantly male punk scene plagued with sexism.

Riot Grrrl “created a space for that type of art,” referring to the darker, politically-motivated and womxn-centered pieces. Flipping through the pages, readers would discover comical, sassy, crude and even provocative photographs, artwork and articles.

“It’s art that is provocative,” Cordovez said. “Really bluntly saying how difficult the female experience can be.”

As zines grew in popularity and Riot Grrrl reached the mainstream press, however, many female authors were criticized and discredited for their work, according to Grinnell College.

With modern music, a hint of Riot Grrrl can be heard and sensed. The music once produced during the Riot Grrrl era has an ongoing influence on the current music scene.

“I feel like there are bands that embody a lot of what Riot Grrrl was trying to achieve, so I think that Riot Grrrl is alive because the point of it is to make space for women in the punk genre, and there are still people doing that,” Cordovez said.

Contemporary artists such as Starcrawler, Sleater-Kinny and The Linda Lindas invoke a similar spirit within their music, allowing the essence of Riot Grrrl to remain today.

The movement held a captivating grip on society, establishing a prevalent and safe space for womxn within the punk scene, pushing back against hypermasculinity and creating provocative and engaging music.

“I think they made progress — it helped pave the way for women to feel comfortable to make music and take part in the music scene,” Cordovez said. She said there is still progress to be made toward creating a more inclusive space for womxn and other marginalized groups within the music industry.

Check out the playlist below to hear some Riot Grrrl anthems along with other songs and artists who invoke a similar feminist energy in their music.